African leaders’ peace mission to Ukraine and Russia last week was greeted with firm refusals from both sides when it came to calling a cease-fire.

The African delegation—including the presidents of Comoros, Senegal, South Africa, and Zambia as well as Egypt’s prime minister and envoys from the Republic of Congo and Uganda—held talks with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on Friday and Russian President Vladimir Putin on Saturday in an attempt to mediate an end to the war.

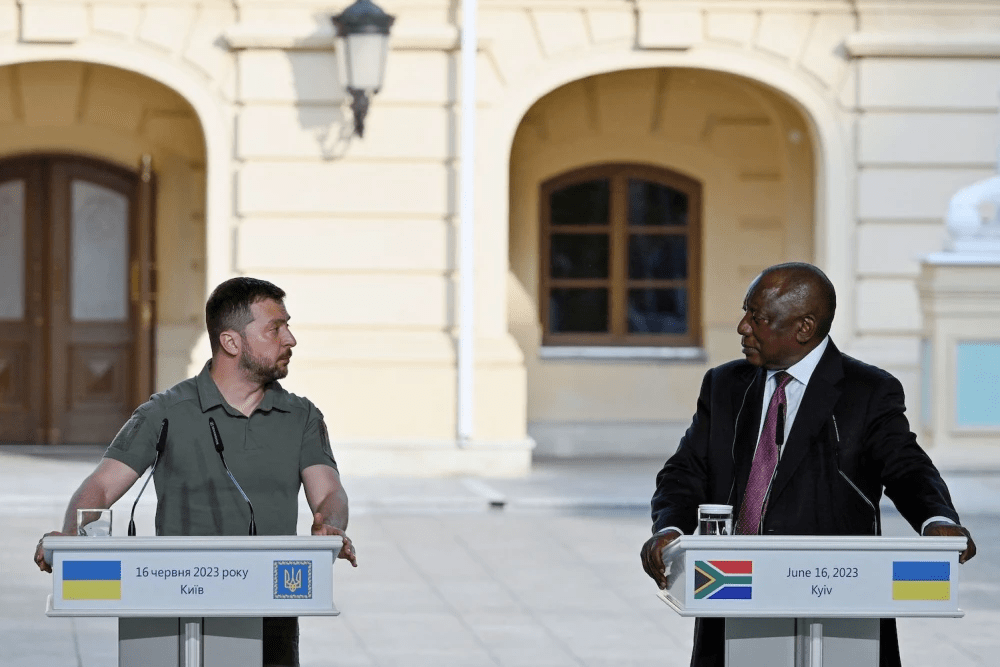

The group’s arrival in Kyiv was marked by Russian air raids. Zelensky underscored that his country would not negotiate while Moscow continued its invasion.

“To allow any negotiations with Russia now, when the occupier is on our land, means freezing the war, freezing the pain and suffering,” Zelensky said in a news conference after the meeting.

Senegalese President Macky Sall responded, saying: “We do understand, Mr. Zelensky, your position because your country is occupied, and for you, military action is a way out of the situation. But we are thinking that when you’re fighting, you still probably need to have place for a dialogue.”

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, and Republic of Congo President Denis Sassou Nguesso pulled out of the mission hours before departure. (Museveni was diagnosed with COVID-19 while Sassou Nguesso had lobbied without success to delay the peace mission due to the launch of Ukraine’s counteroffensive.)

The delegation has said African neutrality in the war and soaring global food and fertilizer prices, which have particularly impacted Africa, puts them in prime position to mediate “for de-escalation.” Sall said: “We don’t want to be aligned on this conflict. Very clearly, we want peace. … That’s the African position.”

It was a sentiment echoed by South African presidential spokesperson Vincent Magwenya in a video posted to Twitter before the meeting. “This mission serves to seek a road to peace that will alleviate the suffering that has been experienced by people in Ukraine,” Magwenya said. Indeed, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who led the delegation, sought to strike a neutral tone and quoted Nelson Mandela several times during the news conference with Zelensky.

“This conflict is affecting Africa negatively,” Ramaphosa said.

For many observers, three of the nations involved are not neutral—Egypt, South Africa, and Uganda are closely tied to Russia—Cairo and Kampala through arms purchases and Pretoria through the BRICS grouping of nations and an alleged shipment of arms that recently caused a diplomatic spat with Washington.

Ukraine has made significant efforts to woo African leaders, knowing that the continent could be key in propping up a heavily sanctioned Russia. Even so, the timing for this peace mission was disastrously misjudged: In early June, as Kyiv began its counteroffensive, a major dam held by Russian forces in Ukraine’s south collapsed, with Kyiv accusing Russia of intentionally blowing it up.

Despite an economic nosedive caused by chronic energy shortages in South Africa, Ramaphosa’s African National Congress party has busied itself with finding ways of avoiding the arrest of Putin when Johannesburg hosts the BRICS summit in August. The second Russia-Africa summit takes place next month in St. Petersburg. Ramaphosa also announced the peace mission just days after the U.S. ambassador to South Africa had accused the country of supplying weapons to Russia, which South Africans officials denied.

Even before heading into Ukraine, Polish authorities had refused to allow about 100 South African security officials and around a dozen journalists to get off a chartered plane at Warsaw airport, leaving them stranded for 26 hours on the tarmac. Poland’s foreign ministry issued a statement saying that “dangerous goods were on board the plane” and that South African officials had not notified them beforehand of additional “persons on board the aircraft.”

The South African government said these were security guards and weapons supposed to accompany Ramaphosa into Ukraine. Ramaphosa’s security head accused Poland of racism because Polish officials refused to accept paperwork for the weapons and of trying to “sabotage” the mission.

The African delegation had proposed a 10-point plan for de-escalation in which Moscow would withdraw its forces from occupied Ukrainian territory, respect sovereignty, and allow a prisoner exchange, the return of children taken from Ukraine, and the free flow of grain and fertilizer to the global market.

But there is little chance of the Kremlin withdrawing as Ukraine demands. Moscow insists that Ukraine accept Russian sovereignty over the lands it has occupied and that it not join NATO.

Putin said the West, not Russia, was responsible for the sharp rise in global food prices and that Moscow was not preventing any Ukrainian children from returning home. “We took them out of a conflict zone, saving their lives,” he said during his meeting with the delegation.

Putin has sought to capitalize on Africa’s historical ties to the Soviet Union, when the leaders of African independence movements sought and received help from Cuba and Moscow. But as Ana Naomi de Sousa writes in Al Jazeera, at the time some members of the Non-Aligned Movement “saw both Soviet and Cuban intervention as another form of colonialism.”

While the visit was unlikely to change the positions of either Ukraine or Russia, the view from most African officials I’ve talked to is that each side is fighting an unwinnable war and some form of dialogue is necessary. Whether the African delegation should be leading that dialogue is open for debate. Many citizens of countries in Africa believe that the continent has enough of its own problems and leaders should prioritize mediating the conflicts in Sudan, Congo, and others across the Sahel.

Source : Foreignpolicy

Add Comment